President Trump has shaken markets with a slew of tariffs — real and threatened — on U.S. imports. Declaring “Liberation Day,” he promises billions in duties, a manufacturing renaissance, and an end to “unfair” free trade. Once unthinkable, protectionism is now reality.

What does this have to do with online learning?

For over a decade, U.S. online higher education has operated under its own internal “free trade agreement” allowing institutions to enroll students across state lines: The National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (NC-SARA). Advocates trumpet its efficiency, but critics warn of lost state control. A tariff hawk might see trade deficits or “degree dumping.”

Are some states disadvantaged by NC-SARA? Could today’s quiet consensus become tomorrow’s flashpoint?

A Big, Beautiful Deal

Before NC-SARA, colleges faced a confusing web of rules governing online enrollment across state lines. Definitions of “physical presence” varied by state: advertising, faculty residence, server location, or even student practicum arrangements could trigger cumbersome regulations. Some states treated simply enrolling a state resident in an online program as “physical presence.”

The enrollment surge during and after the Great Recession of 2007–09, combined with the rise of for-profits and the mainstreaming of online learning, spurred the Obama administration to demand stronger oversight. States scrambled to define their regulations, and schools raced to comply — often at great cost. Some built whole compliance offices, while others barred student enrollment from certain states.

Out of this chaos came what many thought impossible: an interstate compact. NC-SARA launched in 2014 and soon every state joined, except for California. States agreed to minimum standards, designating home-state oversight (along with NC-SARA) for out-of-state activity. The result: fewer approvals and booming online enrollment.

Looted and Pillaged?

Just as U.S. manufacturing saw winners and losers under free trade, NC-SARA has produced its own imbalances.

Figure 1 shows each state’s online learning “trade deficit,” comparing out-of-state enrollment of state residents (online “imports”) to the enrollment of out-of-state residents in in-state online programs (“exports”). NC-SARA data includes nearly all accredited schools in each state, combining undergraduate and graduate online enrollments.

Figure 1.

How to read Figure 1? States on the top of the chart post a “trade surplus” — they enroll more out-of-state residents in their own online programs than they lose. States on the bottom show a “trade deficit” — more residents enroll elsewhere.

The location of an “online giant” in a state explains the surplus in New Hampshire (Southern New Hampshire University), Arizona (Arizona State University, Grand Canyon University, University of Phoenix), Utah (Western Governors University), D.C. (Strayer University), and West Virginia (American Public University System (APUS)), among others. Large military installations partly explain deficits in Texas, California, Georgia, and the Carolinas.

But for other states, such as Nevada, Washington, New Jersey, and Michigan, does a large online learning trade deficit reflect lack of investment in in-state online programming? It might be judged a public policy failure to have such a high volume of educational dollars leaving the state.

States that are home to an online giant or two might appreciate the boost in tax revenue, but their presence obscures the trade balance with respect to other institutions. Remove these giants, and the trade picture flips: New Hampshire’s ratio drops to 0.25. The same applies to Maryland, (0.36, after removing University of Maryland Global Campus), Minnesota (0.66, after removing Capella University), Utah (0.59, minus Western Governors University), Virginia (0.30, minus Liberty University), and West Virginia (0.71, minus APUS).

California, Coming Home

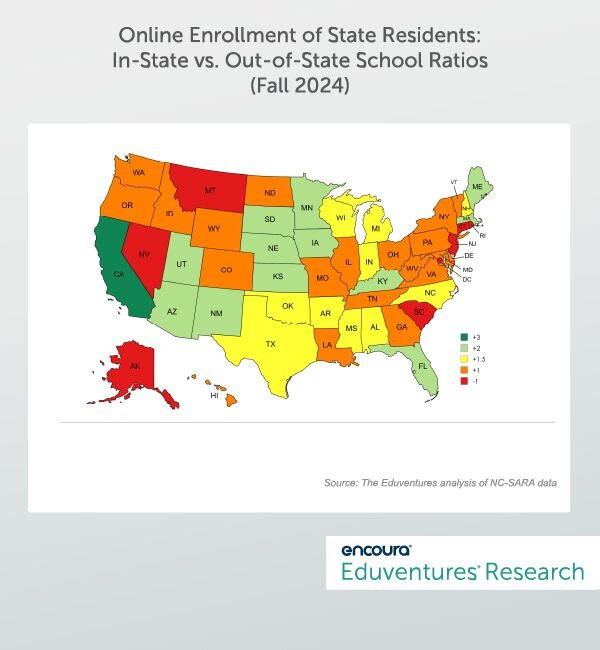

Another way to view online learning “trade” is to compare how many state residents enrolled at in-state schools versus out-of-state ones. Figure 2 shows these ratios range from nearly 3:4 to less than 1:1 — revealing wide variations in how states serve their own students online.

Figure 2.

California, the only state not to join NC-SARA, has the “best” ratio of residents served by in-state schools. Is it because California is not being “ripped off” by “unfair” free trade policies?

Not really. California’s Bureau of Private Postsecondary Education requires out-of-state institutions with no physical presence in the state, but enrolling California residents online, to register. But public and private nonprofit institutions are exempt. For-profit schools, by contrast, must register, but the process is simple and inexpensive. As of now, some 130 for-profit institutions are registered, including all the leading online schools. A ballooning budget deficit in California may encourage more out-of-state schools to target The Golden State.

Nonetheless, out-of-state schools report enrolling fewer Californians online than you might expect. California’s population is 26% larger than Texas’, yet non-Texas schools report 3% more Texas-based online students than non-California-based schools report Californians.

Non-California institutions may market less aggressively in the state, and many nonprofit schools may not realize their scope for action.

The Bottom Line

In 2012, before NC-SARA existed, 59% of fully online students were enrolled at an in-state school. After a decade of online “free trade,” this percentage is actually higher, at 63%.

At a national level, it is hard to argue that NC-SARA has favored the biggest online schools at the expense of others. The compact has simplified operations for all institutions and widened consumer choice. Over the same period, all states saw increased investment in online programs by local schools.

It is also difficult to conclude that students have been “ripped off.” NC-SARA handles complaints from out-of-state students: some 350 complaints have been received over the past decade. Out of millions of enrollments — and among complaints resolved — 72% were decided in favor of the institution.

During the Biden administration, the U.S. Department of Education, encouraged by the likes of The Institute for College Access & Success, toyed with the idea of diluting NC-SARA and boosting state autonomy — in the name of consumer protection against “predatory” institutions — but nothing came of it. Whether NC-SARA will be emboldened or incinerated by Trump’s promised regulatory bonfire remains to be seen.

The lesson from 10 years of NC-SARA? States with too few in-demand online programs (or programs that are poorly marketed or unduly expensive) attract disproportionate out-of-state competition. Prospective students benefit from fewer “trade barriers” to online learning but will “buy local” if there are good options. Hybrid programming might prove a strategic way to lock in in-state business, so long as student experience enhancements outweigh inconvenience.

In most states, a majority of residents in online programs are enrolled at in-state institutions, but in eight (the “red” states in Figure 2), this is not the case. Several others are close to the line. Renewed investment in online offerings, rather than exiting NC-SARA and erecting trade barriers, is likely to be the best solution. But a contrarian lawmaker, in a state with a yawning online learning trade deficit, might want to tie new funding for local schools to barriers to entry for “predatory” outsiders.

Online learning disrupts higher education’s place-based center of gravity. So far, co-location of online students and schools has been a winning formula, and state policymakers see more benefits than drawbacks in online “free trade.”

But is it inconceivable that a state would leave NC-SARA in a protectionist mood? Stranger things have happened.