There is a growing tension in higher education. More people are deciding not to attend, yet 76% of adults still agree that education beyond high school offers a good return on investment.

And the data is convincing. On average, the more education one receives, the more earnings one achieves over a lifetime. Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW) pegs median lifetime earnings of bachelor’s holders at $2.8 million compared to $1.6 million for those with a high school diploma and $4.7 million for those with a professional degree.

But the value of higher education is increasingly in the crosshairs.

Higher Education Enrollment Pressure

The last couple of years saw many would-be college prospects—particularly first-generation, low-income, and underrepresented minority prospects—driven out of the college pipeline as health, economic, and familial concerns sprung from the pandemic. But enrollment pressures were not born from the pandemic alone; challenges can be traced to the prior decade when higher education enrollment rates began to stall.

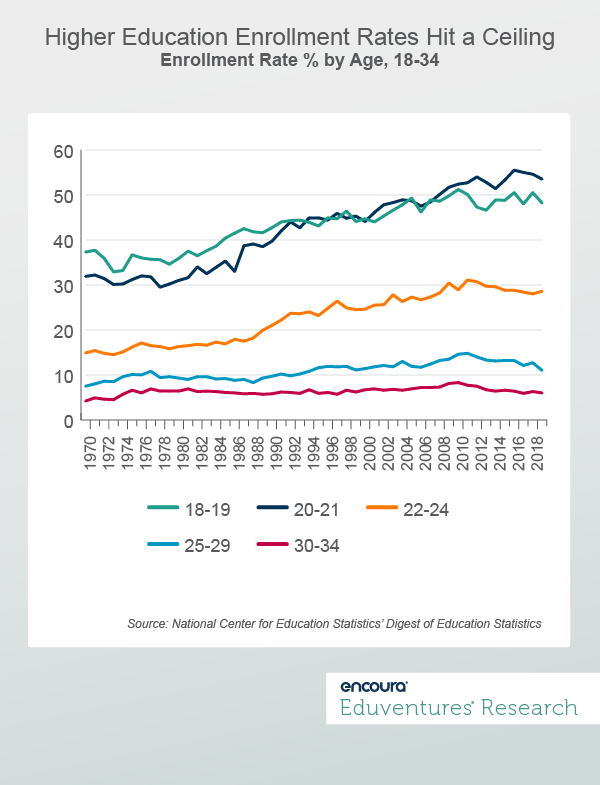

Figure 1 plots higher education enrollment rates between 1970 and 2019 across different ages.

Higher education enrollment rates peaked and then stagnated, or declined, even prior to the pandemic period across key age cohorts. Some trends aren’t that surprising, like the older-aged (or adult) cohorts declining in tandem with strong economic gains in the 2010s. But even the high-school-to-college-going cohort (18 to 21-year-olds) has seen some enrollment rate erosion. What is going on?

New findings from a Gates Foundation study, “Exploring the Exodus from Higher Education,” which surveyed high school graduates who decided not to attend or dropped out of two- or four-year schools, offers some insight. When given a list of potential reasons for not attending or completing a college degree program, 38% of respondents said it was too expensive. This was followed by those who said it was too stressful (27%), that it was more important to get a job and make money (26%), and uncertainty about their majors/future careers (25%). Notably, two of these top four reasons are related to money concerns while the other two are related to the stress and uncertainty that can come with such a big investment.

On the ROI front, two findings from the Gates Foundation study are striking. Thirty-eight percent agreed that “getting a college degree is worth the investment because after I graduate, I will be able to have a career that allows me to be financially stable.” But this was eclipsed by 45% who agreed that “getting a college degree is not worth the investment, because I cannot afford to go into debt when I am not guaranteed a future career path.”

Here it is clear that more people choosing not to enroll, or who have dropped out of college, hold a high-level of uncertainty about higher education’s return on investment.

The Other Side of the Coin

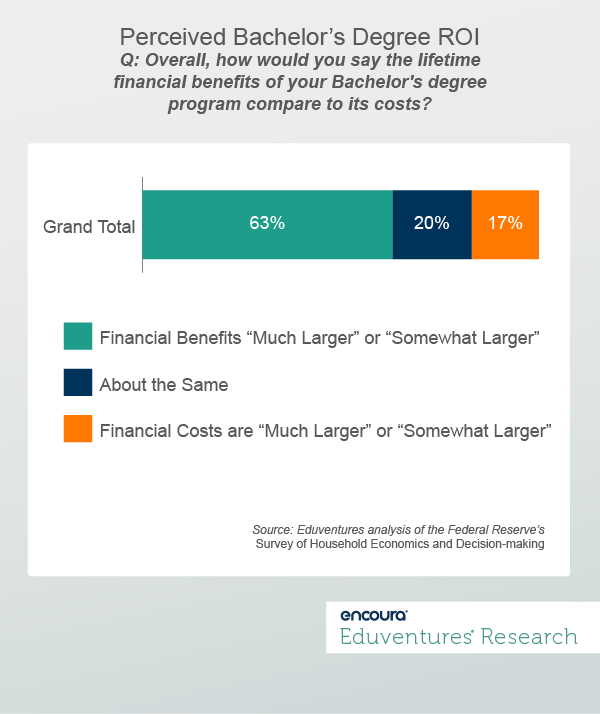

This sentiment greatly contrasts with those who have enrolled in and successfully completed bachelor’s degree programs. The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Household Economics and Decision-Making provides perceived ROI insights for this group. When asked how lifetime financial benefits compare to the cost of their degrees, 63% of all bachelor’s holders reported that lifetime financial benefits are “much larger” or “somewhat larger” as shown in Figure 2.

This figure jumps to 83% when including those who judge the lifetime financial benefits and the costs to be “about the same.” Significantly, just 17% of respondents reported the costs of their bachelor’s degrees outweighed the financial benefits. This even marks an improvement from 2014, the first year this question was asked by the Federal Reserve, when 20% of respondents reported bachelor’s program costs outweighing their financial benefits.

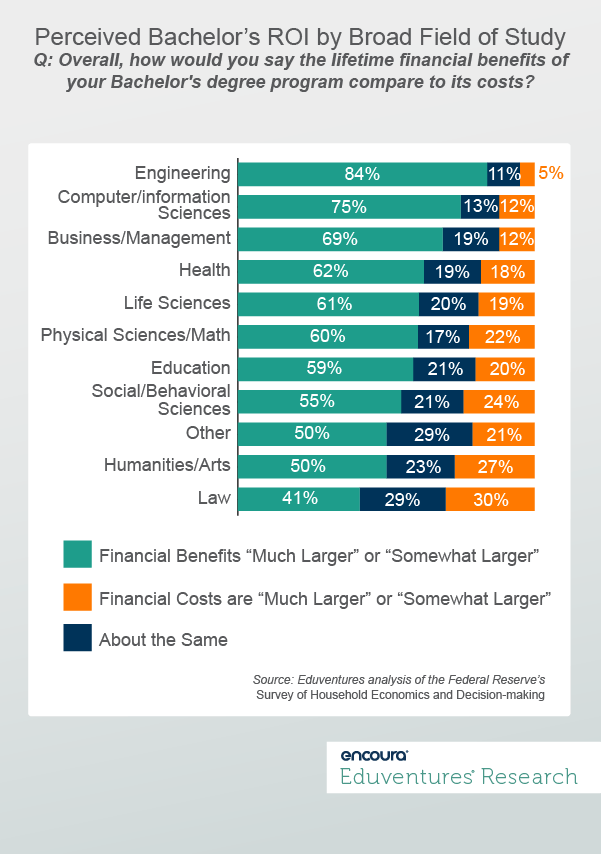

We know that field of study greatly influences potential earnings. While Georgetown’s CEW reported a median of $2.8 million in lifetime earnings for all bachelor’s holders, it also found that median earnings range from $3.8 million for engineering majors down to $2 million for education majors – only $400,000 more than the average for those with a high school diploma only. So, it follows that field of study also influences perception of bachelor’s degree ROI.

Figure 3 breaks down the findings from Figure 2, the average, by broad field of study.

Of note, at least half of respondents majoring in each field, except Law, reported greater financial benefits compared to costs. But it is also clear that more people who majored in fields leading to higher earnings like engineering, computer/information sciences, and business reported larger financial benefits compared to costs, while more people who majored in fields leading to lower earnings like education and the humanities reported larger costs compared to financial benefits.

The Bottom Line

On the whole, those who have been successful in higher education report higher perceived ROI while those who choose not to attempt, or were unsuccessful in, higher education are skeptical of the ROI offered. This makes a lot of sense. But given this, institutional leaders need to ask – have we done enough to prove our ROI?

With enrollment rates sputtering across much of higher education, it appears not. And, with an impending demographic cliff and adult enrollment dependent on the ebbs and flows of the economy, it’s critical to tackle this essential question.

Schools must internalize what is keeping people away—cost, stress, money, and career uncertainty—and use data to tell the overall positive story that higher education’s value, as defined as ROI in this case, persists among those who have gone through it and looks even better within certain major tracks. Start by addressing the following questions:

- Are we able to describe the value, not just the cost, of higher education?

- Are we able to define our school’s ROI in detail?

- Are we able to speak to program-specific outcomes and move beyond the aggregate?

- Are we talking about outcomes and using data to show, not tell?

- Do we link prospects to high ROI fields and clearly describe how we support them along the way?

Finally, thought needs to be given on how these conversations are framed. ROI can be a data-driven conversation that can feel cold or impersonal. Schools should use real stories to help illustrate and put real faces to success stories. Of course, while we reported on bachelor’s holders for much of this Wake-Up Call, not everyone wants or needs a bachelor’s degree, so these questions should be asked across postsecondary credentials and pathways.

Never Miss Your Wake-Up Call

Learn more about our team of expert research analysts here.

Eduventures Senior Analyst at Encoura

Contact

Thursday, November 10th, 2022 at 2pm ET/ 1pm CT

This webinar will present parent and student price sensitivity data that explores this question. We’ll also examine the changing landscape of institutions that have initiated tuition price resets. Join us as we discuss how to understand what best-in-class tuition models will look like in the future and what practical steps institutions can take now toward that end.

The Program Strength Assessment (PSA) is a data-driven way for higher education leaders to objectively evaluate their programs against internal and external benchmarks. By leveraging the unparalleled data sets and deep expertise of Eduventures, we’re able to objectively identify where your program strengths intersect with traditional, adult, and graduate students’ values, so you can create a productive and distinctive program portfolio.