These are dangerous times for the least selective private institutions among us. This segment of the nonprofit sector lost 7% of its traditional-aged enrollment during the pandemic. Since 2022, 40 nonprofit private schools have merged, closed, or are intending to do so—36 of which are least selective private institutions. In stark contrast, only one four-year public campus has merged in the same timeframe.

The crisis in this sector will only deepen as demographic challenges reduce the addressable market; these 36 institutions represent the canary in the coalmine for a deeper crisis of value (or lack thereof).

Last month, we wrote about how the current environment has reshaped the traditional undergraduate student pipeline. Today, we’ll take a closer look at how the outcomes of these students are shaping the fates of colleges and universities.

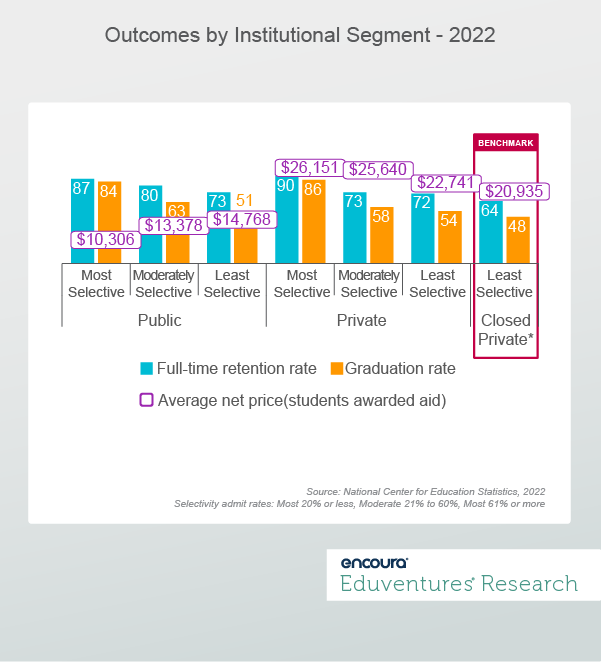

Figure 1 shows the first-year retention rate, six-year graduation rate, and net price for students receiving financial aid across six institutional segments, including public and private, and ranging from most to least selective. It compares the outcomes metrics of these six segments to those of the least selective private institutions that have now closed.

Figure 1.

This is clarifying data. It’s easy to see why students are flocking to moderately and most selective publics. These institutions have good outcomes at a good price. The least selective institutions, public and private, struggle the most with measures of persistence and completion.

On retention (72%) and graduation (54%), least selective privates are on par with least selective public institutions (73%,51% respectively). On net price, they offer less value than least selective publics ($22,741 vs. $14,768).

The least selective privates that have closed their doors are slightly lower in cost ($20,935) than those that remain open. But they are significantly worse in retention (64%) and graduation (46%).

Based on these metrics alone, it’s hard to make a case for attending a least selective private institution. Institutions that have closed have offered comparatively little value for their students. This message—that they are unable to deliver measurable outcomes at a good price—is a hard message for institutions to hear.

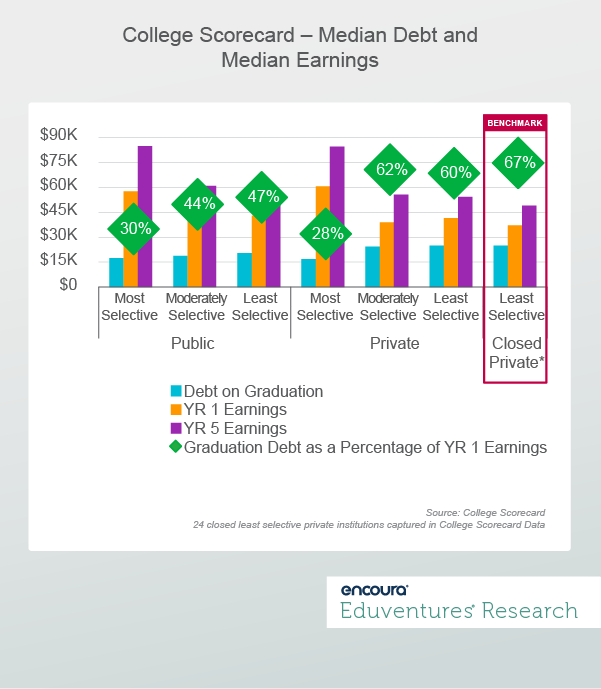

Figure 2 shows how each of these same six institutional segments, plus the least selective institutions that have closed, have performed on student debt and median salaries.

Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows that the most selective institutions, public and private, offer the best value for the money in terms of low debt loads relative to first-year earnings. The most selective institutions also offer the greatest increases in salary over the first five years of earnings for graduates.

Among least selective institutions, public and private, starting salaries are lower, and earnings growth is slower. Focusing on the least selective private institutions, the lower earnings expectations (year one = $41,468; year five = $54,214) are compounded by much higher debt as a percentage of first-year earnings for graduates (60%).

And as we might expect, the value story is the worst for institutions that have closed. Their graduates earned $37,058 in year one and $48,993 in year five. Debt as a percentage of first-year earnings was a very high 67%. Now add in that these institutions graduated only 48% of their students. It’s a grim value story. What student would logically choose to apply to or attend a low value institution when they could attend one that offers more?

We should allow that the least selective institutions serve a disproportional percentage of first-generation college students, those from low-income households, and those from historically marginalized populations.

These are the very students who need the economic push of a successful college education the most. These are the students who struggle the most to graduate from college. These are the students who deserve a higher level of support to become successful college graduates. Struggling colleges should focus on developing minimum standards for outcomes to turn the corner on real value for students.

The weakest value performers in undergraduate education are being pushed to closure. The revenue crises that often drive small undistinguished privates out of business are the symptoms of an underlying disease that we could call value anemia – the lack of good outcomes at a good price.

The Bottom Line

Closed institutions are still a small part of the overall undergraduate landscape. But the evidence is clear. Other institutional segments are not immune to value anemia. Many more institutions, especially the least selective privates, already have this disease and need to treat it before it becomes terminal. What is the treatment?

Here is what it is not:

- Making unconsidered price reductions. This is a value story. Always consider both sides of the value equation. Improve your outcomes and consider how price fits into the value story.

- Marketing your way out of trouble. Telling your institutional story better will only get your institution so far if your institutional story is marred by value anemia for your graduates.

- Becoming more selective. Let’s not equate poor outputs (outcomes) with poor inputs (students). For most institutions, becoming more selective is not a viable solution.

Here is what it is:

- Improving the value equation from both sides. Focus on the full value equation: your institutional outcomes relative to price. Improve your outcomes and consider how price fits into the value story.

- Aligning undergraduate programs and experiences to student needs. Students will get to the right outcome if your educational opportunities support their pathways. Before you tell the story of your institution, improve the story of your institution.

- Doubling down on student success. Take a fresh look at student success efforts relative to your student body. What will it take to improve retention, graduation, and earnings given the students you serve?